How we got here

Why do we use videos and photos in addition to words in news? One of the reasons is because text has some limitations.

Words can only express so much information to the audience, so we add media such as audio, video, and images. When we want to more accurately or quickly bring a viewer into a specific situation, whether a protest or sporting event, it helps if we can use a medium that accurately captures the scene.

Different media have different strengths and weaknesses. Newspapers in the early days included illustrations that were created from engravings based on hand-drawn illustrations. Later, in the mid-1800s, engravings were sometimes based on photographs. These engravings communicated a scene or an object quickly and effectively to the reader. However, they were time-consuming to make and were rarely used to capture “on the ground” news situations. As the art of photography developed during the late 1800s and half-tone printing became possible, newspapers began to print photographs. These images showed a scene with more immediacy than an engraving. Think of the front-page images of wartime Europe.

Moving images - from jerky film strips to slow-motion videos - have the potential to convey even more information than stills. The eye evolved to follow motion, so we are drawn to a picture moving on a screen.

As we moved from analogue to digital media the quality of movies changed considerably. When we could store images and videos digitally, their number and quality was limited only by the number of bytes of information that a disk could hold.

The web of the early 1990s was primarily text-based because the wires that connected computers couldn’t yet quickly carry large amounts of information. If you think of it as a bridge, early Internet connections could only handle the weight of humans on bikes with loaded panniers, not large transport trucks full of cargo. Any images that were uploaded were low resolution (compared to today), and therefore easier to download. Even so, it could take several seconds or even minutes to download a photograph via a modem.

The increasing quality of photo and videos sensors has led to higher resolution media and a need for larger bandwidth capabilities. During this time our connections having grown from dial-up speeds of 50 kilobits per second to up to 1000 megabits (1 gigabit) per second; a 20,000x increase.

Thinking back to our bridge metaphor, we now have a bridge which is a well-built steel structure that can withstand a steady stream of fully laden transport trucks.

Problems in media

One of the interesting constraints to sharing video and images on the web is that, since its inception, video uploading and downloading has been limited by bandwidth. The capabilities of your line into the internet predicted your end experience when trying to view media on the Internet.

This limitation has meant that only in the last 10 years has video really taken off as an online medium. YouTube and other other early video sites proved that leaning hard on the barriers to speed enabled the creation of brand-new media experiences on the web.

We’ve seen a very similar constraint with cell phone bandwidth over the last decade: only fairly recently have sites and mobile apps started doing heavier media-focused work.

While we are consuming more video and audio than ever before, it’s important to remember that busy people won’t always want to stop what they’re doing to focus on complex media involving video on their phones. Any media project that you build should reflect your appreciation that not everyone is in a quiet place, or can afford deep attention. Respect your users’ available time, variable connection, and data charges.

Where does the future lead?

As we develop better standards for audio and video, and as bandwidth becomes less of a constraint, expect further experimentation into what audio and video can (and must) be used for. As Wifi coverage increases our devices will become more constantly connected. At the same time, our devices’ memory capacity is increasing, allowing us to save more content, so we will likely see more capabilities for offline access.

Building technology so that media like audio and video can be viewed offline is something that will likely see more attention in the future. This will trend will follow our devices and their storage abilities, as well as the capabilities of more native apps building in offline modes as a main feature.

Examples and Code

Popcorn.js

Site: popcornjs.org

Github: github.com/mozilla/popcorn-js

Popcorn.js’s goal is to make video more interactive. Currently the amount of information that a viewer can get from a video is finite and dependant on the content of the video. With Popcorn.js you can add many different types of media such as maps, links, and images to help create a better and deeper story.

Soundcite

Site: soundcite.knightlab.com

Github: github.com/NUKnightLab/soundcite

Soundcite allows for audio to be linked inline with the text. This can be powerful when tied to a story that involves audible components that can greatly add to a story such as interviews, protests, or music.

- Tutorials

- Examples

Hyperaudio

Site: hyperaud.io/

Github: github.com/hyperaudio

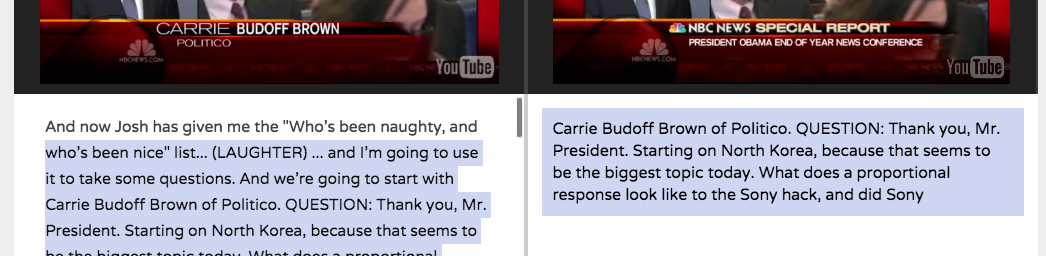

Hyperaudio is a both a web tool and library to make video and the language used within the videos more interactive. The Hyperaudio pad allows you to take parts of different videos by selecting specific parts by their transcripts and remixing them.

youtube-dl

Site: rg3.github.io/youtube-dl

Github: github.com/rg3/youtube-dl

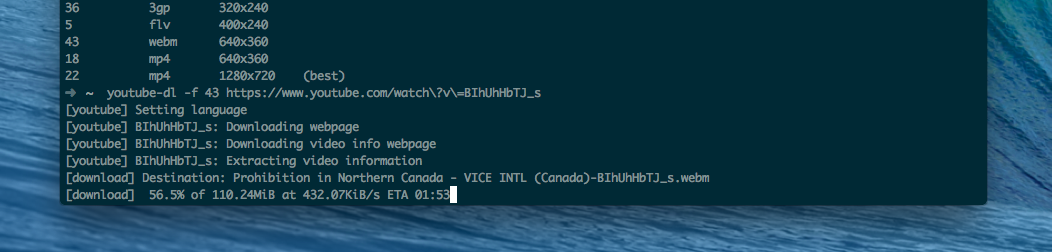

Youtube-dl is a command line tool that makes it easy to get a video from websites like Youtube, or Vimeo. It can also do audio sites like Soundcloud.

If there’s a piece of audio from a protest, it’s easy to just scrape the audio from a Youtube video.